Don’t Set Your Next CEO Up to Fail

At the heart of many botched appointments is the lack of a clear mandate.

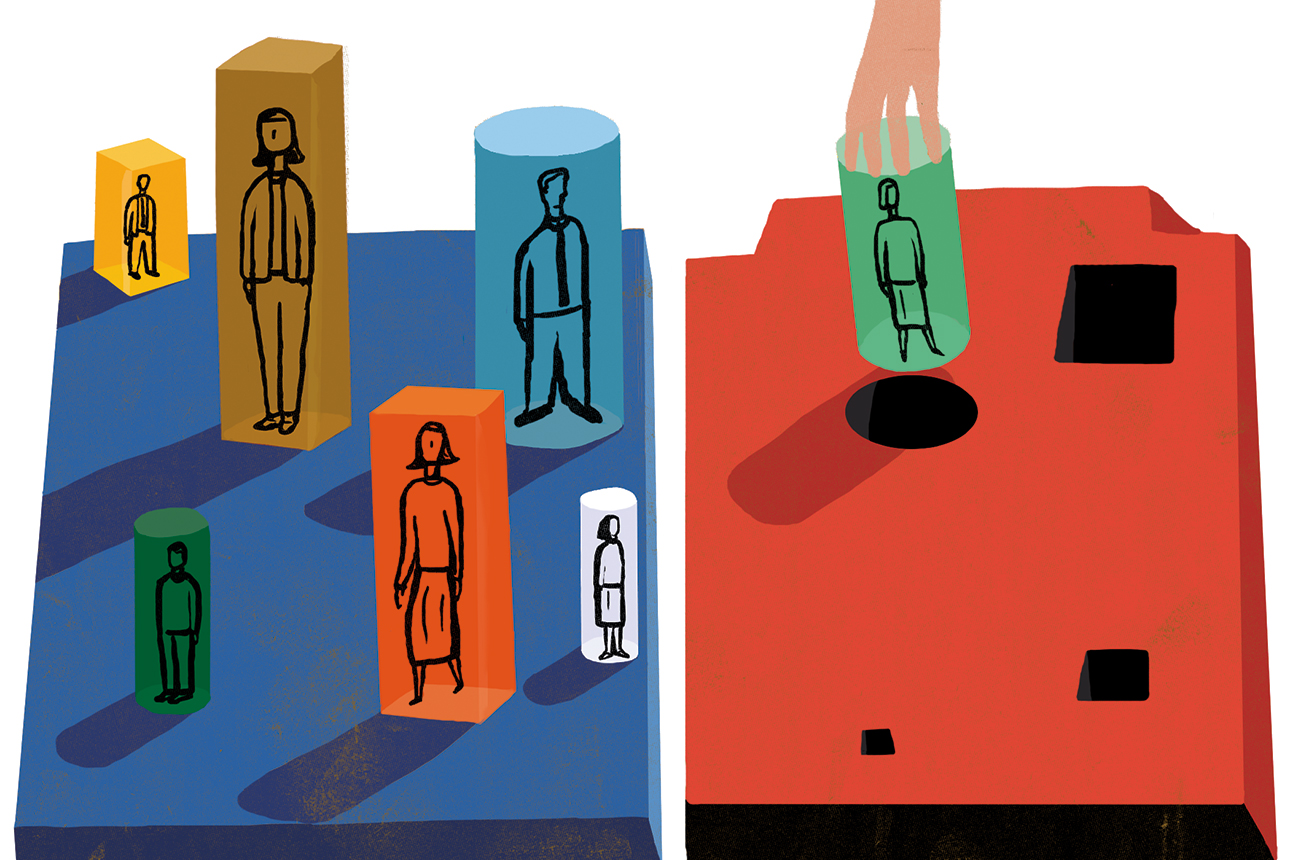

Image courtesy of Jud Guitteau/theispot.com

After a long and distinguished career in logistics and transportation services, in 2015 Per Utnegaard was appointed CEO of Bilfinger. The job was clearly a big challenge. Bilfinger, once Germany’s second-largest construction company, had been having financial difficulties for a number of years, and a prior CEO succession had already proved unsuccessful when Roland Koch, the former minister-president of the German state of Hesse, failed to orchestrate a turnaround.

Less than a year after Utnegaard’s highly publicized appointment, he left Bilfinger, and the search for a new CEO began again.

We shouldn’t be surprised. CEOs come and go — even seasoned executives with previously unblemished track records. According to a study by Equilar, the median CEO tenure at S&P 500 companies has shrunk to about five years, and we have found in ongoing research that more than 15% of all CEOs depart within two years. The best-laid plans — especially succession plans — often fall apart when they encounter reality. What is surprising is how shocked and appalled boards are when their CEO choices fail — sometimes repeatedly.

The financial costs of these poor choices are enormous. To find the right CEO (or one who appears to be right), boards routinely bring in search firms whose fees, related to the compensation of the people recruited, can easily reach seven digits. You don’t want to repeat that drill year after year. And the costs extend beyond the selection process: A study by PwC consulting company Strategy& estimates that companies lose more than $100 billion in market value annually through botched CEO appointments.

Of course, the organizations suffer as well. If there is a vacuum of leadership at the top, uncertainty pervades the ranks, and the vision becomes unclear. That is typically followed by a standstill in development, the departure of key talent, and a decline in financial performance.

With so much at stake, what can companies and their boards do to increase the odds of success?

At the heart of many failed succession processes is the lack of a clear mandate. Boards often have only an implicit sense of what they want the CEO to do — in particular, how much they want the strategic direction and organizational model to change and how they expect the new leader to accomplish that.